Distant Riders

by Robert Estermann

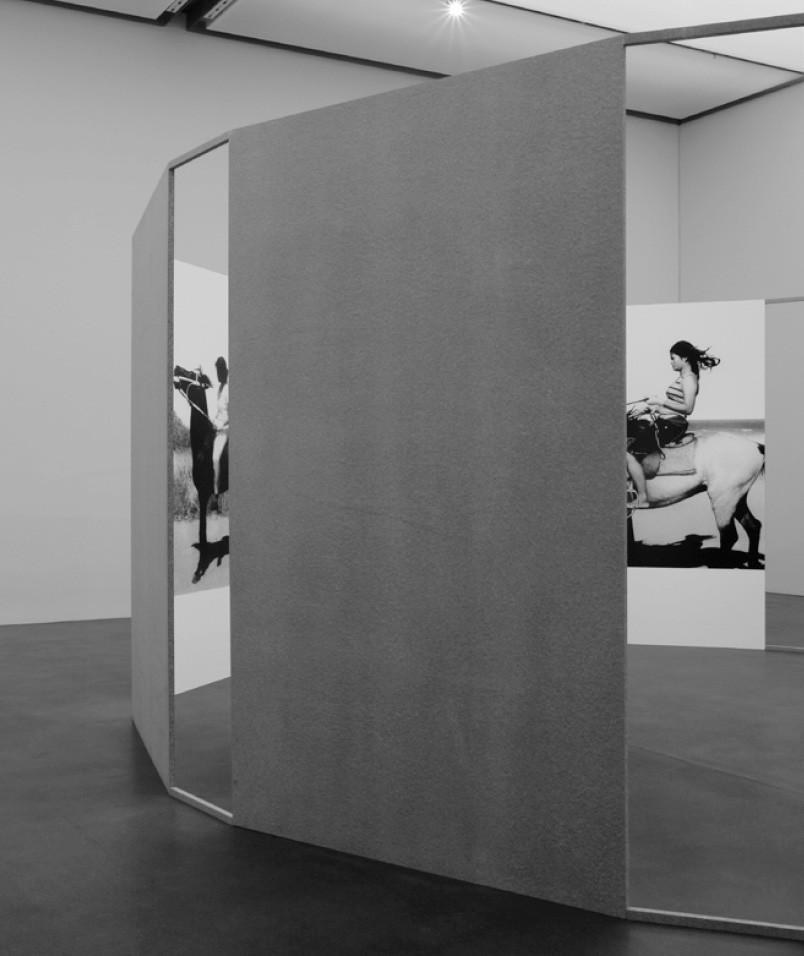

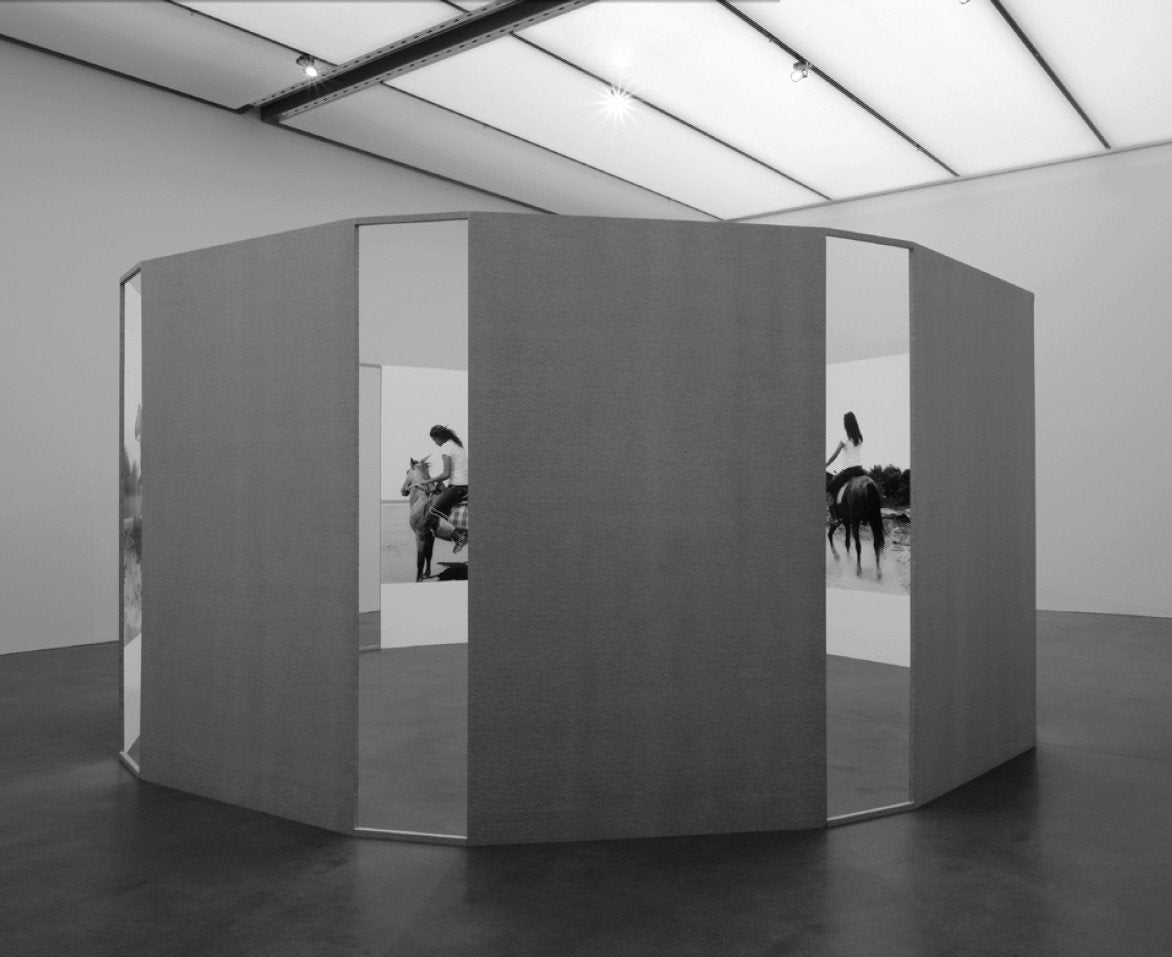

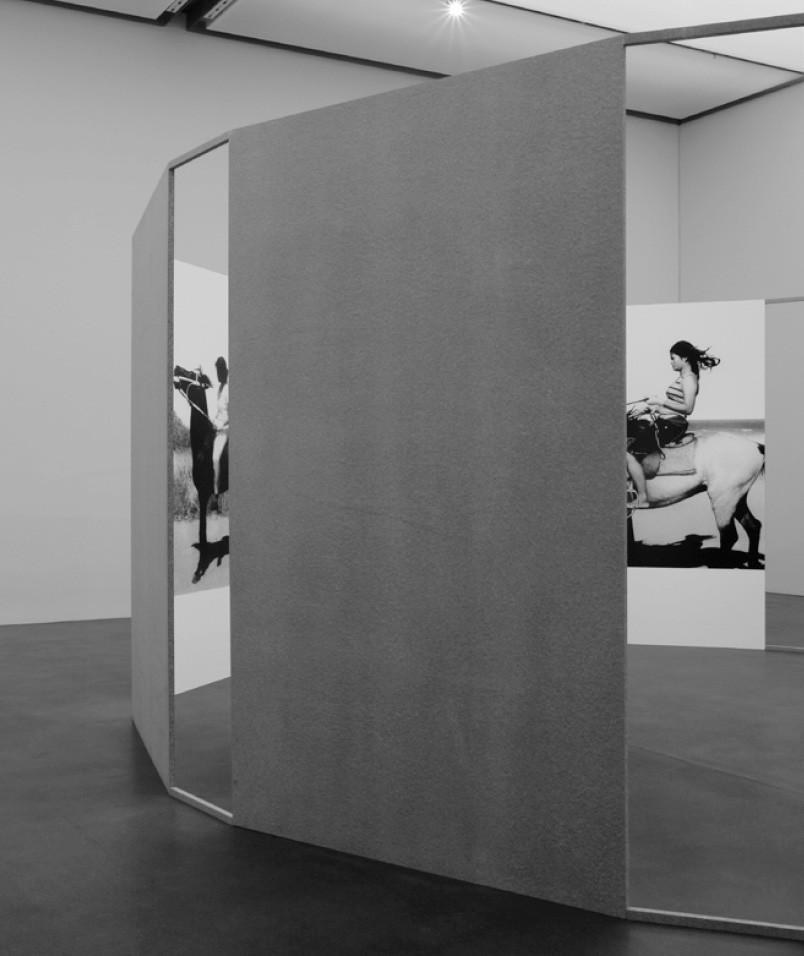

Installation: 9 digital prints (260 x 150 each) on wood and steel construction, 260 x 580 x 580 cm

This work was inspired by the “Zoetrope”, invented by William George Horner (1786-1837) in the 1830s, an optical device that produces the illusion of motion, often equipped with the image sequence of a galloping horse. The images of female riders on secluded beaches in Thailand were taken by Estermann himself and reflect the hallucinatory aesthetic of photography in the 1970s.

shown in:

“Robert Estermann. Manor Kunstpreis Luzern 2007”, Museum of Art Lucerne, Switzerland (solo show)

“Swiss Art Awards 2007”, Art Basel, Basel, Switzerland

„In this larger-than-life zoetrope, the individual riders merge, so to speak, into a single rider. The landscape in the background of the nine photographs also seems to coalesce into a hyper-landscape. The background does not refer to a concrete geography more closely defined in temporal and spatial terms, but is rather the visual correspondence of a more diffuse kind of “beach-likeness” with a heavily metaphorical element: distance, culturally protected zone, state of emergency. Once again we are dealing not with a literally political discourse - for which read sexually reformist, generally “liberationist” – although it is also possible to discern an atmosphere of this kind in Distant Riders. This atmosphere is produced by the hallucinatory effect of the signifiers of the 1970s which Estermann is quoting here, apparent in the slightly voyeuristic gaze with which the riders enter the field of vision. One consequence of this hallucinatory treatment of signs may be that another context interposes itself over the sexually reformist and generally “liberationist” discourse of the 1970s: the question of the economic, political or even erotic relationship between humans and animals. But how does this theme arise, when it is neither formulated as an ethical programme nor idealised as a mythical unity from the past? As has already been discussed, the slight sexualisation of the motif of the girl rider is too faint to locate the sequence of images in the sphere of the obscene, let alone the perverse. And the atmosphere of the images, with their location in a distant, undefined coastal zone is too restrained to be subjected to a moral discourse. One key may be the landscape. Its significance as a trope may be better understood if we compare it with the function of the scenic refuge zone commonly featured in dystopias: usually this is portrayed as a zone contrasting with the civilised space, which is why it is depicted alternately as an inaccessible desert far from city life, as in Brave New World, as a hidden, protected forest at the end of the last railway line as in Fahrenheit 451, or as a distant coastal zone as in Distant Riders. This counter-world is rich in sensations and full of sensual freshness (in Fahrenheit 451, this is represented by the constant light snowfall in the protected zone of the forest). But as it is freed from the everyday, and its inhabitants are often in a kind of temporally and/or culturally exceptional condition, there is always something unreal – phantasmatic – about the counter-world. This makes its psychological function all the more important: it allows the citizens to experience sensomotoric renewal or even awakening (as opposed to social anaesthesia), psychical continuity (as opposed to schizoid fragmentation), and develop ethical care (as opposed to moral cynicism).“

Excerpt from: Improper Thinking by Daniel Kurjakovic

in: Robert Estermann, Pleasure, Habeas Corpus, Motoricity. The Great Western Possible, ed. Susanne Neubauer, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Museum of Art Lucerne, edition fink, Zurich, 2007, ISBN 978-3-03746-105-1